Gentoo, Gentoo. Ah yes, Gentoo. Gentoo is my favorite Linux “distribution”. I’ve mentioned it before!

Manually configuring a kernel is often seen as the most difficult procedure a Linux user ever has to perform. Nothing is less true – after configuring a couple of kernels you don’t even remember that it was difficult ;) 1

…consider Gentoo’s behemoth

portage(5).2

That last one is a little underhanded. Not for calling portage “behemoth” – I think that anybody who has used Gentoo knows exactly what I’m talking about.

$ man portage

PORTAGE(5) Portage PORTAGE(5)

NAME

portage - the heart of Gentoo

DESCRIPTION

The current portage code uses many different configuration files, most

of which are unknown to users and normal developers. Here we will try

to collect all the odds and ends so as to help users more effectively

utilize portage. This is a reference only for files which do not al‐

ready have a man page.

No, you see, for Gentoo, they need a behemoth like portage, because Gentoo is hardly a distribution at all. It’s more like a collection of tools that people can use to help ease the headache that would be maintaining their own Linux From Scratch (LFS) installation.

The biggest selling point is its toolchain for compiling everything in your system from source, with all the relevant configuration options you might have in mind. You can build all your applications without the dependencies for functionality that you don’t need. Better yet, you can build your applications without that functionality altogether! For me, a nice one here is compiling GNOME keyring3 without any of the GUI components on my server. Its dependency on pinentry is obliterated, and so is the seemingly endless list of Qt5 codependencies.

Another big one is that changes to configuration files between versions are actually obvious and handled well. I find that when I use a Ubuntu-like distribution, it’s a serious mess trying to figure out what changes with each upgrade; and especially difficult to find out what is new in my configuration file. With Gentoo it’s just a matter of running dispatch-conf and paging through the changes.

It’s also good if you’re concerned about the freedom of software. You can specify which packages are available to you by which license they use. Don’t want GNU/Linux? Then just compile all your software with musl!4

Using open-source to build your system leads to some really neat paradigms that you don’t see in other distributions. The great one is that your whole system is viewed as a source tree, hence the semantics of the command emerge. It makes things fairly reproducible so long as you version your config files.

There are many things about this approach that irk people, though. For the true Gentoo experience, you compile everything from source. Everything.

An actual, official part of the installation process that the manual really likes to encourage is compiling a custom Linux kernel for your system. Think about it: you can create your perfect, purpose-built system! Its kernel is designed with you in mind, because you are the one who configured it! Think of the possibilities!

- Zero memory on-free like iOS does now

- Poison the stack returning from a kernel call (every time)

- Remove support for filesystems that you don’t care about

- Make functionality that you personally deem non-essential into a module

- Remove support for emulating 32-bit binaries… Maybe you have a special reason.

- Round-robin scheduling for processes…?

For most desktop users, that last one is just comedy. There is something to be said, though: installing Gentoo and configuring a kernel was the first real exposure I had to the different scheduling algorithms and memory fragmentation mitigation techniques I was learning in university. You really can use round-robin scheduling if you build the kernel yourself. Whether that’s a good idea is up to you.

But let’s take a step back and enjoy a cool, refreshing glass of perspective. Should we really be having people configure their own kernels?

No. We really shouldn’t, in my opinion. Maybe not even developers. I view kernel configuration in the same way that I view hand-rolling cryptography: it’s something that really only a qualified expert should be doing. There’s so many ways that you can absolutely botch your system by configuring something in your kernel wrong. I did so in my first Gentoo installation many, many years ago trying to set up Docker. A few wrong configuration options and suddenly my system is running significantly slower than it did post-install. Networking, especially, was behaving strangely. I hadn’t kept any notes and, consequently, had no luck retracing my steps. I’m willing to bet the average amateur OS enthusiast distro-hopping left and right would make the same mistakes.

There’s a few small parts that are fine to tweak, like the ones I mentioned above (zero-on-free, less filesystems, more modules, etc.), but past those is nothing but suffering. Configuring a kernel to support virtualization is a minefield. Even setting up something like iptables can be a pain to get right.

Even the argument that compiling all your software yourself will significantly improve performance might be misguided. Removing support for certain big features like Xorg might improve performance on a server that I only want to use for a few applications, but for the average enthusiast desktop user with their Xorg and their BSPWM or Dunst, I don’t anticipate much improvement over the same DE on Arch or Artix.

Where the most improvement might be seen in that case is in really complicated software – something like a web browser, but then you start running into compilation time issues. Even if your hardware is high-end, compiling Firefox from source is so notoriously laborious that Gentoo had to add a binary package. I tried compiling it once on my i7-4770K desktop, and a few hours5 into it I decided to bite the bullet and download the binary.

But, this might be getting off track. I like Gentoo. No – I LOVE Gentoo. Seriously.

It’s absolutely a contradiction. Even with all the time it takes to install. Even with the inevitable problems you’ll encounter when upgrading. For all the compilation time for relatively minimal gain. There’s not too great an argument for why people use it. It’s flashy and brutish; it’s impractical; it’s trading on the margin for pennies; it’s just shy of unusable for anyone else and if you change one environment variable it might all crumble to pieces. You know what that sounds like to me? A project car.

People love project cars! They tinker with them to learn, lovingly fix them when they’re broken, and they drive them because it’s fun.

If there is such a thing as the “Murciélago of Linux”, then Gentoo is like the Datsun 500 you’ve had sitting in your garage for the last 10 years. Absolutely impractical for the average user, more maintainable than a high-end sports car, but still just as fun.

Looking at it this way, it becomes less about performance and “cool points” and becomes much more focused on enjoyment of the user.

For enthusiasts with enough wherewithall, I don’t think it’s a bad hobby to manage your system at the level Gentoo demands. If anything, it’s educative. Years ago when I absolutely butchered my daily driver’s network connectivity by messing up my kernel when installing Docker, I was frustrated, but I had fun figuring out what went wrong with minimal information to go off of. That’s a skill that ended up serving me well after graduating.

For an uninitiated user just looking for a cool system, though, the Gentoo manual can be like a guide to Frankenstein’s monster. If you didn’t understand the risks going into it, you’ll sure as hell understand them coming out of it.

But it’s ultimately your project. You don’t need to justify why you’re doing it.

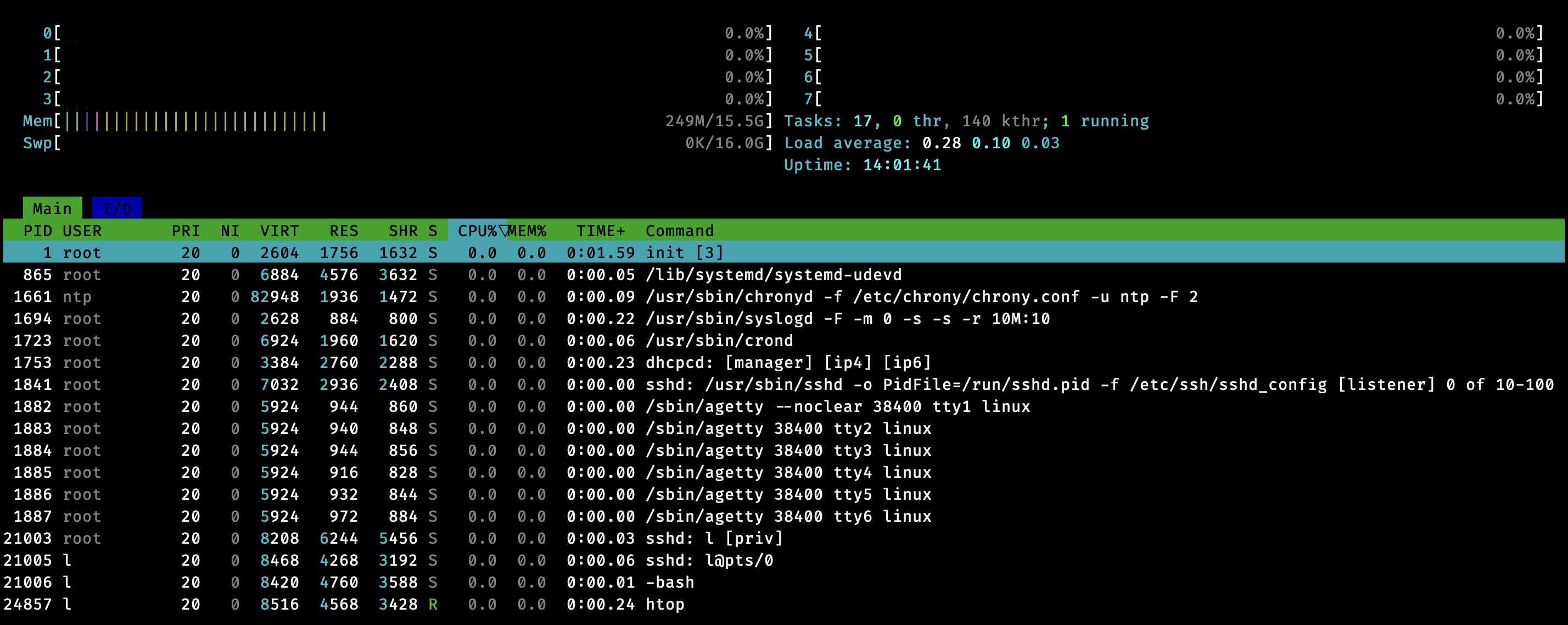

…and, there’s certainly a case to be made for checking your system htop output to see a comically low number of tasks at idle.

I’m just going to say it - I get excited when my system breaks.

Oh? What’s that? The sweet siren’s call beckons me once again? What amusements await us this time? Unsatisfied dependencies? Slot conflicts? Perhaps, I daresay, a circular dependency or two? Nothing gives me a jolt like watching portage spew forth a slew of errors in beautiful 256, knowing that my baby needs me. Pop the hood, interlock fingers && flex, and get to work. The satisfaction after resolving blocked updates and seeing the packages that were previously taunting you getting emerged is comparable only to the most worldly and carnal pleasures. When I see that there is a new news item, there’s a decent chance that I may literally scream with excitement. I woke up in a hospital after receiving word of the 17.0 -> 17.1 profile upgrade. They had to sedate me because of the blind rage I flew into knowing that my system was unattended, rotting away on the ancient and deprecated 17.0 profile. Nobody knows your system like you, and the bond that I’ve developed with my distro over the years is irreplaceable. I’ll never go back.6

-

And I’m glad they killed it in RHEL 8! Ding dong the witch is dead. https://access.redhat.com/solutions/4491691 ↩

-

https://www.reddit.com/r/copypasta/comments/gs715n/i_use_linux_as_my_operating_system/ ↩

-

Yes, hours! I let it run most of the day before giving up. ↩

-

https://www.reddit.com/r/Gentoo/comments/bzyc3f/im_just_going_to_say_it_i_get_excited_when_my/ ↩